On the Ghats, Benares. c Siofra O’Donovan

Morning prayers and ablutions at Ma Ganga, on the Ghats. There is nothing quite like the morning light at Kashi (old name for Benares)

Benares. Kashi, the city of Light, is the old name for this oldest continually inhabited city in the world. It is as filthy as it is holy and the most prestigious place in all India to die: if you do die here, your soul will go straight to heaven, over the vast belly of Mother Ganga, the river where Hindu pilgrims batthis . Once, I had bathed in the river, when I was here with Leszek, my Polish boyfriend, many years before. Dressed in white, I plunged in, to the amazement of the Indians who rarely saw a westerner take the risk of diving into, (supposedly), one of the most polluted rivers in India. Every white person would tell you it was filthy. My sinuses were so blocked I couldn’t hear anymore, I was so poisoned by the air in Kathmandu where we had gone to get new visas for India. When I came out dripping, I felt as if my body had absorbed every vitamin and mineral there was to absorb, through the poisoned net of the river. By the time I had dried off, my sinuses had unblocked. So there it was. Mother Ganga had cured me, whether by faith or foolishness, I did not know.

This time in Benares, I didn’t take the plunge. I was here to publish my travelogue about Tibetans in India with an eccentric, but well-established publishing house in Durga Kund, just around the corner from the great Durga Temple. I made my way from Sarnath, ten miles south of Benares, in a Rickshaw, wedged in the insane medley of Benares traffic. I could hardly breathe by the time I got to the publishing house. My head swarmed with the sound of beeping in the clatter of traffic. Beeping is a music in Benares. It is a pleasure. It is not for faint-hearted, as I saw one westerner write on a postcard home. Beeping is a statement:

“I am here, you are here, we are all here. Who will move first?”

But nobody can move, most of the time, at least not in a continuous line, because everyone is going in different directions at the same time and it is quite normal to travel down the other side of the road in your vehicle, while the others travel up it. Delhi traffic was polite and constrained compared to this. The closer you get to the Gods, it seemed, the more the rules go out the window. And Benares is India’s city of the Gods.

I found my editor behind a pile of books in his dusty office. He was an Englishman, called Christopher, who had been in Benares for forty years. He had long white hair, large, drooping green eyes and a set of rings that would put him in competition with Gandalf. (But did Gandalf wear rings?)

“I’m very swamped.” he said in an English accent that had survived his forty Indian years. He glanced up lazily at his pile of books. His accent was faint. I was surprised, most Englishmen never lose their accents. He moved slowly around his desk, from behind this pile of books, and shook my hand. Later, he took me out on his Enfield, which I rode side saddle- when in Rome- to the nearest and best South Indian diner, where we had Tali and he broke it to me that I would be editing my own book. He simply didn’t have time.

“There are some very good hotels on the Ghat.” he said languidly flapping a ringed finger across the demented, steaming traffic.

My stomach burned with the Masala Dosa I had just eaten with him: too damn hot. I went off to find a hotel, most of which seemed to be filled with Westerners stoned out of their minds. Bonga bonga city, Shiva’s city, this was a great place to smoke and lean back at night on the ghats and listen to the drums of the evening pujas break out over the Ganga river. Time out. Relax, like Shiva. Drink Bhang. Smoke Ganja. Watch the bodies burn on the Burning Ghats, two hundred or three hundred a day. Watch life and death meet on the banks of the River Ganga.

The Burning Ghats. Around 200 bodies burned a day. Straight to heaven.

But that’s not why I was here. I was here to work, and to study. I needed to find another mother. Nobody knew me here, nobody would know I was recovering from a relationship with a very quixotic, wily Tibetan lama. I found myself in a Bookshop on Assi Ghat. The owner, a young Indian man, told me about a family who had a paying Guest House down the road behind the temple. A family. That’s what I wanted. I needed that. I wanted to be fed. I even wanted to be scolded and told not to go out, at night. My bookshop friend was, it turned out, the nephew of the owner of my publishing house: Rama ji He brought me to the sleepy side street where the Mishra family lived. Immediately, I was home.

“Good Evening,” said Mr. Mishra, as he got up sleepily from his hammock, wiping the dust off his kameez. He had a square-shaped head with big brown eyes and eyebrows that whipped upwards like Dali’s mustache.

“Come, come. see the room.”

Up a flight of banister fewer stairs, was the room: empty, but lilac colored.

“I’ll need a desk,” I said.

“No problem,” he said.

“I’ll need a light,” I said.

“No problem.” he said, wagging his head.

“I’ll need a chair.” I said.

“No problem.” he said.”Only one thing-” he said.

“Benares is a very bad place. Very corrupt.There is only a little power.”

Most of the time there would be no light and no fan. I wrote and edited my book by candlelight in the heaving heat of a Benares spring, on a wooden table the size of a small pillow. I wrote everything by hand.

Reading the news in Benares, BHU

He brought me downstairs to meet ‘Mummy’ and ‘Pinky’, his delightful unmarried daughter who always wore pink. It would be one hundred and fifty rupees per night for the room and they decided that they liked me so much they would feed me in their sitting room. Mummy made me paranthas (potato pancakes), dal (lentils), and loki (An Indian vegetable reputed to be very good for the stomach). She made the most divine Kir, (Indian rice pudding), with the faintest smell of nutmeg and cardamon, that I have ever tasted. She was so different from my Amala up in Darjeeling, who had made me thick thukpa soups and meat dumplings, momos, when I lived with the Tibetan family by the tea gardens. Now I ate the finest vegetables from wheeling traders on the streets that had vegetables spilling over the edges of their carts and prams: aubergines, loki, bindhi, potatoes, carrots, lychees, mangos, radishes, tomatoes and onions.

Mummy prayed for me as she did her morning salutations to Durga, her own goddess. The invincible Durga rides a tiger, slays demons and carries fierce weapons. This was the kind of mother I wanted: one that would protect me. And Mummy did. She made sure I never ate outside the guesthouse. She fed me her divine Kir, and taught me to say: “Me Buk Hung” which means, “I’m hungry”. It was music to her ears, that admission. To my own mother, it was a burden, an impossible request. A hungry child was a bother. In the quiet privilege of my Georgian childhood, food involved sighing, cursing and pots banging. Sometimes, plates flew across the kitchen. My father hid behind his newspapers in the drawing room by a crackling fire until the dinner was produced: the preparation was too fiery to be around. Mealtimes were often silent, nothing but the clinking cutlery for conversation.

My Durga Mama could think of nothing more pleasurable than feeding her little ones. That I was a little one, albeit in my early thirties, was her delight. No other guest was fed there, but me. Mr. Mishra, my Papa, was also delighted with me: I don’t smoke the ganja, I didn’t play music in my room, and I didn’t have a boyfriend. I sang, and wrote, and edited in candlelight. I ate with my Mishra family. I wrote home.

“It is very good. You will be married, it will be sure thing in two-three years you will be married. It is better to have no boyfriend, to be prepared. Pinky, she doesn’t have a boyfriend you see. She will marry next year, you see.”

But Pinky was twenty two. I was ten years old than sweet Pinky. I kept my ex boyfriends locked away. Papa did not know about them, and he never would. I kept writing, made friends with some monks. Maye I lived in a kind of cell. I made friends with my neighbour, a Thai monk called Pi, whose English was hard to understand at first, but he had great humour, and over the months in Benares, we shared many stories. He was motherless. He came from the Burmese border from a village full of violence and witchcraft. He and his fellow monks were studying at the Benares Hindu University, doing MA Degrees in various religious subjects despite being in-proficient in English and Hindi. Pi would cycle to the University in his saffron robes with a headful of ideas. They were a serene and gentle group of monks, far more, I felt, than the earthy, practical Tibetan monks who seemed to be so much more worldly- and who have a great interest in motorbikes and Bollywood music.

A Haiku for Pi:

Young monk cycles

To philosophy class

Robes catch in the spoke

Pi the Thai monk, a very dear friend from the time of checking into the Mishra Guesthouse on Assi Ghat

Poor Mummy, in the Mishra Guesthouse, had lost her fourth child, followed by a hysterectomy. She would hold her big belly that hung out over her sari midway and groan. It was an injustice, she felt, to lose her womb and that sweet child. It was something she never got over: motherhood ripped out of her. My own mother had had a hysterectomy, but she never groaned about it: it was a practical matter for an impractical thing. I thought of all the goddesses in India, all the shrines and temples across India to the Great Mother in her different forms: Durga, Kali and Parvati, Shiva’s wife. The fierce and the gentle: all the aspects of femininity. So revered are the Goddesses of India, and yet her own women are so often denigrated, considered obsolete without a husband, and disposable when they become widows. Sati is the act of throwing yourself on your husband’s funeral pyre. It’s not so common today, but it exists. Daughters are a heavy liability for an Indian family: they carry the dowries. Daughters with paltry dowries are frequently murdered by their in-laws. India has a vast pyre full of aborted daughters.

Me and a Thai monk called Rumphet, outside Benares Hindu University Campus. I’m trying to look very proper and all that as I’m standing with a monk.

The Thai monks and I took an early morning boat on the Ganges River, watching the sun rise and spill red light over the waters. It was like drifting over the border between life and death, watching plumes of smoke rise up from the Burning Ghats, where the first bodies of the day, wrapped in linen and ghee, were set on fire, the smoke of corpses rising to meet the first airs of that Benares morning while we drifted past. I felt held by Mother Ganga and grateful for the time I had cured myself in her waters of sinusitis from Kathmandu, city of my ex partner, the renegade lama. The river was full of flowers from the morning offerings and I floated in and out of thoughts about what it was that I might regret at the end of my life and I knew with brutal clarity that I would have to have a child to hold.

On the Riverboat, on the Ganges, Benares

My dear Mishra family in Benares took it upon themselves to nurture and protect me in my vulnerable pre-marital state. After that dawn sail in a riverboat on the Ganga with my Thai monk friends, I had a dream that I was dying and that my one regret was that I did not marry my first love, Tomek. An Indian fortune teller in his mother’s kitchen had told us, when we were seventeen, that we would marry. But we did not- we took separate paths. On this morning in Benares, I regretted it, and I regretted the trail of turmoiled relationships that followed that first love. Parents and priests had had no bearing on the matter. Here in India, it was as it had been once in Ireland. Parents and priests and astrologers took hold of the destiny of unmarried children and made it their business to seal lasting deals.

In Benares, on the Ganga river, I resolved to start all over again. I would write, paint and sing my way out of the old twisted roads that I had followed and set myself free of those ancient traps in my mind. I would carve a new path and move into new horizons of love and fortune. I had a new family, after all. The Mishras. I was training for new ground. On my way to the publishing house for meetings about my manuscript, I would send my letters home from Asi Ghat.

Dear mother,

I love going to the temples. I love the festivals of music, listening to Ragas into the morning hours, the smell of incense and rose petals all around me, drinking chai from clay pots, watching the flower and candle offerings float out under the moon over the Ganges as the pilgrims pray that they will be carried home by the Mother again…. I love the family that I am living with here, who feed me rice pudding that makes Ambrosia creamed rice look like brine. It suits me here. Many people say that Benares is filthy and dangerous and noisy and polluted. But I have found a home here. Besides, I have started to sing…

And I wasn’t in a choir. That was how I’d sung as a child: from Church Hymnals, my tinny voice hidden among the thundering ladies of the Church of Ireland. Now, I had found my own voice. I had a singing teacher called Sanghita Ghosh who was my age, and unmarried, for complicated reasons to do with her dowry.

Sanghita Ghosh, my beautiful singing teacher in Benares

It was not an enviable position to be in, in this deeply conservative and ancient city. But if you were a musician in Benares, you could be excused for anything. Those from Musical families were in a caste of their own. On the other hand, if you weren’t, you had no right to study and play music. I had seen the finest Tabla player in my life play in London a few years before: Pandit Sahai. He was from a Benares family. That Sanghita was from a good family of musicians was her saving. She could keep her honour in tact. She taught foreigners how to sing Indian Ragas. I learned to sing songs to Krishna. Her friends would watch me as she dragged me gently up and down the scales of the Ragas : Sa Re Ga Ma Pa Da Ni Sa! They said I had a sweet voice, and I held my songs to my chest like little gifts, because I would keep them forever. My Benares songs, which one day I would sing to my own child.

Me in the STD booth, talking to my Mother that fateful day, when the Temple was bombed. Ok, STD is not a disease, its an old Indian phone booth for International Calls, pre-internet days. THere are none left.

It was 7th March. Mother’s birthday. My Mishra Mummy had fed me my parantha and curd that morning. I went to the STD booth to call my mother but she could hardly hear me over the crackling line, and the torrent of babbling Indian voices that sailed in over crossed lines. I resolved to send her a silk Benares scarf that day. Sanghita, my singing teacher and I went to Asi Post Office to check that my parcel to my mother had been sent: if you don’t see the postmaster stamping the stamps, your parcel could end up going out the back door and never leaving the country. It was covered in 5 rupee stamps, like a patch of Indian wallpaper. They had run out of 50 rupee stamps, and this was the result. A silk Benares scarf. Silk, the very thing that held Benares’ society together: in this sublime textile, Muslims and Hindus worked warp and weft together. Except, however, on this day. Mother’s birthday. Today, there were three bomb blasts in Benares. One in the Dasaswamedh area near Godowlia, in the the Cant. Railway station and one in the Lanka area, in the Shiva Temple. Nine were dead. Possibly Al Qaeda. It may have been the recent pact the Indian Government had made with George Bush, they said. This, perhaps incensed the Muslim community, who were so demonized by the War on Terrorism. I had never, even in Ireland, been so close to the site of a Terrorist Bomb.

I went to my publishers and edited by candlelight with my editor in the background, drooped behind his piles of books. Rama ji had just appeared, like the Scarlet Pimpernel. He was the owner, a garrulous and mysterious self made man who dressed like a sadhu in an orange dhoti. He had a long, shiny black beard that he caressed with great care. In the middle of an argument, usually with my editor, he would break out and laugh like a hyena, shattering the office tensions, rattling the fans. My editor would throw his eyes to heaven, and wait, tapping his long ringed fingers on his desk, until Rama ji had stopped. There was nothing you could do, when Rama ji had an attack. You simply had to wait. Everything and everyone waited while Rama’s laughter shook the dust off his vast collection of antiquarian books. Ha ha ha ha HAAAA Ha ha ha ha HAAAA. Mr. Singh would wait at the end of the stairs with a tray of tea, for the right moment to place it on the desk that sat between the Laughing Publisher and his sidekick, Gandalph the Editor.

Pilgrims Book Shop, Benares

Pi collected me from the office that macabre day in Benares, as the dust settled after the bombings and the rumours raged across the old city: who had done this? Muslims? Would there be riots, in this of city of silk, where there had never been conflict between Muslims and Hindus, who wove warp and weft together on the finest silks in all of India? Pi and I took a walk to the Shatha Maked Mandir, the temple where one of the terrorist bombs had gone off. Police were everywhere. The night before, arms and legs and hands were littered in the temple area. Poor villagers had come to Benares for a wedding, (it being the wedding season), and never got to go home. Bombs were begin defused at Viswanath Temple and Dasaswamedh, bombs which would have littered the ghats with broken limbs. All on mother’s birthday.

THe Goddess Durga

On my way home from the scene of the crime, feeling a little bruised and listless, I dropped in on the Durga Temple. Durga, the protectress of my surrogate Benares mother. The pujaris didn’t like it when I visited the temple, but I did so frequently. First, I would visit the small shrine to Sarasvati in the corner: she was the Goddess of learning, art and music who sits on a lotus with a swan, with a vina in her hands. She is the transcendent Goddess of great ideas in art, music and science.

The Goddess Saraswati

She is the great completer of projects. In Benares, I was full of music, ideas, books and paintings and a baby was still nothing but a little echo in my belly. Sarasvati guarded the integrity of my own ideas, and gave me the courage to face the incompetence of my publishers. To me, being in a Hindu temple was an act of defiance to the whole mundanity of western utilitarianism. I loved the wild devotion: the mountains of marigold garlands, the thick smoke of incense, the bowls of coconut milk, the vermillion and scarlet powders for anointing your forehead, the clang of the bell as you entered and left your shoes outside, the throngs of people throwing themselves at effigies and statues, pushing each other out of the way. You would only see this kind of crowd vivacity at a football match or a concert in the west. But here, the frenzy was for the Gods.

Durga Temple, at Durga Khund, just around the corner from my publishers

And though Sarasvati was my friend and my guide, she was not my mother. She is not a mother, as she is the most transcendent of all the goddesses. Durga and Kali on the other hand are wild, ferocious and protective mothers. Parvati, wife of Shiva, is the beautiful mother of Ganesh. Lakshmi, also a mother, is the irresistible Goddess of fortune. Today, on my mother’s birthday, with that little echo in my belly, I did not visit Sarasvati’s shrine. Today, I spoke to Durga, in the centre of the temple. The pujari pressured me to offer money after he had handed me lily of the valley to offer her. In my mind, I told her that I wanted a child. I did not know why, on my mother’s birthday, I made this wish. I knew that I should be careful. I was careful. I made the wish in the silent recesses of my mind, as the bell rang at the temple door, and barefoot devotees came to pay their respects, as the petals of marigolds, roses and lily of the valley fluttered at my feet on the temple floors. I wanted a child. I was telling the Mother Goddess that I wanted a child. Books, paintings , songs and the deeply soporific music of India were taken care of by Sarasvati, in the corner of the temple. I had all of that, I had it in abundance. But now, I wanted creation to move through my very body.

After the disastrous first print run of my travelogue about Tibetans in exile,in which the page numbers were entirely mixed up and the paper was as thin as Gideon’s Bible, I decided to leave Benares. Deep was my regret that I had conceded to publish with the Cowboys in Benares. Everything was upside down and mixed up.

Lost in Shambhala: https://www.amazon.com/Lost-Shambhala-Siofra-ODonovan-ebook/dp/B00Z83VDD

“We will do another print.” conceded my editor, hiding behind his piles of books. And I left, deciding it was better to sing than to worry about my book. It was too tragic to contemplate. Five years of traveling back and forth to India funded by the Arts Council, studying Tibetan, collecting stories from the oldest and feeblest of Tibetan exiles, the finest and most revered of Tibetan lamas, and it had come to this: an upside-down book that looked worse than anything you would have self-published. And this was a reputed publisher in India. Everywhere, chaos is at work in India. There is no stable, rational ground to stand upon. That is the most wonderful and the most terrible thing about India.

Outside the Maharaja’s palace in Benares with my Thai monk friend and Indian police officer

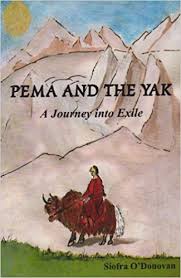

The original travelogue, Pema and the Yak, published 2006 in Benares, India. Pema and the Yak

Keep this going please, great job!