My ideas for books come to me in dreams. When I was living in Kraków, teaching, acting and writing my first novel after graduating, I saw Stanislav at the top floor of his apartment in Salwator, remembering the war. So the story of Malinski began. And when I was writing Malinski in a hut at the foot of the Sugarloaf Mountain in Wicklow, with a field of deer behind me and a dark forest beside me, I had a dream about an old woman living in a hut deep in that forest, who had fled from a war.

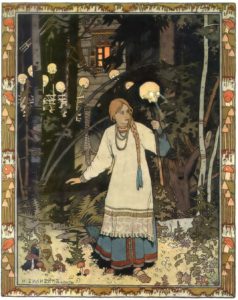

An awful war, in which they burned and gassed those who did not conform…Baba Yaga had resurrected herself in my dream as a Polish refugee who lived in the woods I’d known all my life, in a hut nobody had ever found. She painted pictures…and so the story of The Secret of Pocock Grange began. Not my first encounter with a faery tale, but at last I’d found the genre I loved: Middle Grade fantasy, which captures the twilight age of 9-12, the ‘Coming of Age’ age… everyone from Blue Wing to Frodo to Harry Potter to Red Riding Hood…

Vaselia’s War

Published in the Literary Journal Tales from the Forest, Vaselisa’s War is a retelling of the old tale of Vaselisa and Baba Yaga from Russian folklore. Vaselisa, fleeing a war, finds her refuge is with Baba Yaga…

Published in the Literary Journal Tales from the Forest, Vaselisa’s War is a retelling of the old tale of Vaselisa and Baba Yaga from Russian folklore. Vaselisa, fleeing a war, finds her refuge is with Baba Yaga…

Excerpt

My mother died of fright the night the first bomb dropped. Under a starry sky, a storm of dust fell through the broken window. But before her last breath, she handed me a doll with two button eyes and a ripped cheek, a thing she said belonged to my Granma, and her Granma, and to her Granma, all the way back.

My father had only one leg: he set out on his crutches to replace her. On the first day, he came back with a chicken, on the second, with a donkey from the paddocks and on the third, with Mrs. Ravisham the Widow and her three daughters, the youngest of whom could cook Goulash. I, on the other hand, could not cook an egg.

Read More

Malinski

Malinski is about two young brothers in Lvov, Poland, are separated by war. Henryk Malinski, imprisoned by the Nazis with his mother in the family home — the aura, power, and brutality of the Nazis are brilliantly evoked — flees with her ahead of the advancing Soviets, eventually settling in Ireland, where he becomes Henry Foley, a rakish, boozing academic, and spends his life in denial of, and tortured by, the demons of his childhood. Stanislav takes refuge with a devout and deranged aunt in Kraków, where he lives out the decades of his life — a solemn, gray, and humorless character, a human reflection of the communist state. Half a century later, after the fall of communism, Stanislav receives a letter: Henryk/Henry is coming for a visit. Malinski explores the powerful force of human memory, and particularly its complexity. As each character shows us, there is no real escape from memories, or from the past. It is only as the brothers confront each other and their history that they can begin to find peace.

Malinski is about two young brothers in Lvov, Poland, are separated by war. Henryk Malinski, imprisoned by the Nazis with his mother in the family home — the aura, power, and brutality of the Nazis are brilliantly evoked — flees with her ahead of the advancing Soviets, eventually settling in Ireland, where he becomes Henry Foley, a rakish, boozing academic, and spends his life in denial of, and tortured by, the demons of his childhood. Stanislav takes refuge with a devout and deranged aunt in Kraków, where he lives out the decades of his life — a solemn, gray, and humorless character, a human reflection of the communist state. Half a century later, after the fall of communism, Stanislav receives a letter: Henryk/Henry is coming for a visit. Malinski explores the powerful force of human memory, and particularly its complexity. As each character shows us, there is no real escape from memories, or from the past. It is only as the brothers confront each other and their history that they can begin to find peace.

Part One: Stanislav

Chapter One

I am an old man now. I live here, on the top floor of a tower block overlooking the Vistula. SInce the war, since Mama left. Since the Germans came and th Germans left and the Russians came, scarlet red, and left us grey.

Read More

The Secret of Pocock Grange

Synopsis

Only Granma knows the secret at Pocock Grange. Finella, the gangly, skinny misfit, of Ernestown, is about to find out, after she has had dreams about a strange war and a glimmering ring. Granma and Finella go to Pocock Grange that Hallowe’en. Pocock, the old recluse of Pocock Grange gives them the message Baba Yaga has sent a message through the Old Book: send the girl to the Woods of Nowhere. She is needed. There have been wars, terrible wars called the Steel Wars. Thousands of people have been incinerated by the Steel Man, mastermind of the Wars. Not yet ghosts, they are hanging onto life, encamped at the foot of the Moon Mountain.

Every day, the Fire Master razes tracts of forest to the ground, in search of these Lost Souls, whom he will hand over to Steel Man to turn into robots for his Steel Factories. It is Baba Yaga’s job to get them out. She cannot do this without a Dreamer, who negotiates the Passage out of the Woods of Nowhere, back into the world, where Lost Souls can be restored.

Finella needs a Dream Bag. She needs clean, perfect dreams that cross the threshold between Pocock Grange and the Woods of Nowhere. She needs to mix them into a Potion and carry them back across the threshold, to Pocock Grange, where the illustrious alchemist, Dr. Pocock, will finish the work with the Blue Eagle. Then, the Passage will open and the Lost Souls will return.

Finella’s greatest enemy comes from her own blood: her half brother Edmund is the secret ally and, unwittingly, the illegitimate son of the Fire Master, Lord of the Woods, servant of the Steelman. Together they work to ruin Finella’s attempts to save the Passage, and destroy it from the other side. Baba Yaga, at last back in Pocock Grange, proclaims there is one, last chance: there is a Passage in Shambhala, beyond the Northern Mountains, where no human has ever been. It is up to Finella to dream the future of the world.

The Love Chapter

The Love Chapter the Balcony Project, an Inner City Multi Media Art Project by Rhona Byrne, who commissioned me to write the ‘Love Chapter’. This was recorded by Rose Henderson, and placed into a cube shaped audio box that broadcast different stories and music when activated with the headphone plug. Quite ingenious!

The Love Chapter the Balcony Project, an Inner City Multi Media Art Project by Rhona Byrne, who commissioned me to write the ‘Love Chapter’. This was recorded by Rose Henderson, and placed into a cube shaped audio box that broadcast different stories and music when activated with the headphone plug. Quite ingenious!

About

Brid has lived in Bluebell all her life. Her daughter Caer finds a pewter thimble in her flat, which Brid claims is the very vessel that Tristan and Isolde drank the love potion from, in the middle ages.Brid’s mother survived her father’s drinking years with this very thimble: she administered a ‘love cure’ from it that brought luck to desperate, love-weary people in the locality.

There is a dark secret behind Brid’s father’s story of a young UCD student, secretly a member of the IRA, who was blown up by a mine on the Naas Road in 1922, who left behind him his fiancé who hanged herself in the Rose Garden.Years later, Brid’s mother tells her the story of a young girl called Isolde from Chapelizod, whose lover was killed by a Black and Tan grenade on the Naas Road. Isolde poisoned herself with ammonia. There is a strange connection between the two stories that reveals a terrible secret in Brid’s family, which revolves around the thimble.

Love, both pure and tragic, is explored in this story that is inspired by the infamous legend of Tristan and Isolde.

Read More